This week’s post is a little different, instead of focusing on one named SheHero I want to write a about the SheHeroes who worked in the munitions factories during the First World War, whose names have been forgotten; the Munitionettes. I have recently been able to look into the role these women fulfilled and find out more about what their lives were like.

This week’s post is a little different, instead of focusing on one named SheHero I want to write a about the SheHeroes who worked in the munitions factories during the First World War, whose names have been forgotten; the Munitionettes. I have recently been able to look into the role these women fulfilled and find out more about what their lives were like.

In 1914 approximately 24% of working age women were already employed, they worked mainly in domestic jobs, as shop assistants, or doing simple work in small factory industries. By the end of the war the number of women who had taken up jobs had grown to approximately 1,600,000 – with over a million of those working in the munitions factories. The employment which women found open to them throughout the war not only increased, but diversified, with women doing less of the traditionally female roles they had before the war and taking their place in more male dominated areas.

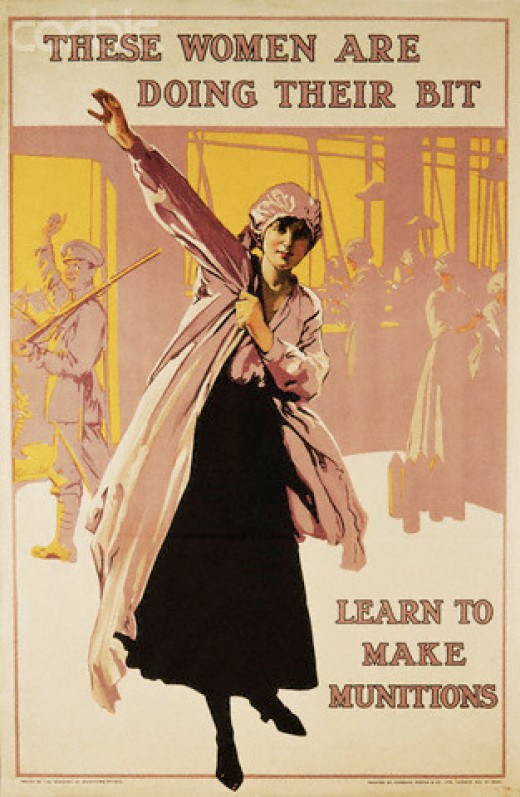

The recruitment of women into the munitions factories and other previously male-held positions grew gradually. The shell crisis of 1915 made clear the drastic need for more munitions and work was stepped up at home. An act was passed which allowed factories to employ more women and so the doors began to open for women to enter the munitions workforce en masse.

In 1916 the Government introduced conscription which saw another 2.7 million men leave Britain, on top of the 2.6 million who had volunteered. This left an ever increasing demand for a workforce, which ultimately women filled.

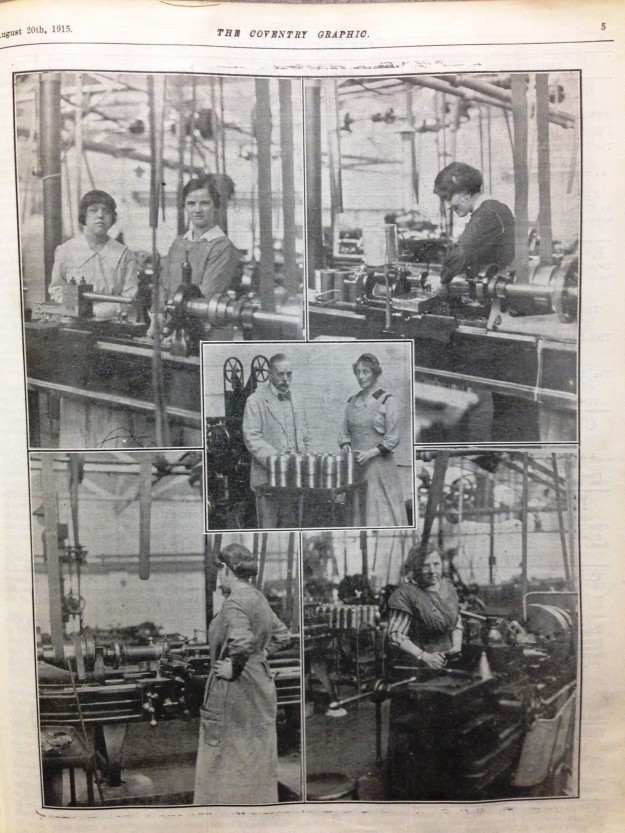

In my research at Coventry’s local History Centre I was able to look through editions of the Coventry Graphic newspaper from 1915-17. The paper focuses heavily on the men: those who were leaving, those returning – often injured, and sadly a weekly rolecall of those who would never return. It’s only towards the end of 1915 that mentions of women taking up absent men’s jobs start to appear:

Women who went to work in the factories could expect to be working 12 hour days for a 6 day week. They often worked on bonus systems to encourage faster working and productivity. Many factories built temporary accomodation to house the influx of workers and nurseries were set up so that mothers could also join the workforce.

When starting out the women often found a mixed response from their male colleagues. There are stories of deliberate sabotage by men who weren’t keen to share their space with women, but on the whole it seems the men appreciated the need for extra workers.

The Imperial War Museum has a fantastic set of oral histories from those who worked in the munitions factories which give colour & detail to what factory life was like. (The quotes I have used in this piece are gathered from these oral histories.) Harry Smith remembers how the men in his factory reacted to the new female workers:

“Well they weren’t as skilled as the men that’d been brought up with the job, but they did just the job that they were told to do. And there [was] more repetition work then than previously in the years before the war. Well, some didn’t – the older men didn’t like it, but some enjoyed it because they, some went to have a drink at night with them, but not me.”

To allow for as many women to enter the workforce as swiftly as possible many skilled jobs were broken down into smaller, more simple tasks that the women could learn quickly. This was known as the ‘dilution of labour’. There was some opposition to this, particularly from unions who feared that this diluting, in addition to the lower levels of pay women earned, would lead to fewer jobs for their male members when they returned from the front. There were of course also those who just didn’t like the idea of women leaving the home at all. The Factory Times magazine in 1916 wrote,

“We must get women back into the home as soon as possible. That they ever left is one of the evil results of the war!”

Muntionettes were paid less than half that of male workers, however striking was made illegal and so many found little recourse to address this unequal pay.

Two women in particular who deserve a mention for their efforts to assist female workers and address the pay issue were Mary Macarthur and Margaret Bondfield (featured on Sheroes a few weeks ago) who were the founders of the National Federation of Women Workers.

The War Cabinet Committee on Women in Industry agreed with equal pay in principle they said, but believed that due to their “lesser strength and special health problems” (?!) the output of women would not possibly be as great as that of the male workers!

Working in the munitions factories came with significant hazards. A now fairly well known phenomenon was the TNT poisoning which turned many women’s skin yellow.

Caroline Rennles worked at the Slade Green Factory in Kent, she remembered the effect of the TNT well:

“Well of course we all had bright yellow faces, you see, ’cos we had no gas masks in those times and all our hair here… The manager used to say, ‘Tuck that hair under!’ you know, and you used to almost look like nuns… So it was all bright ginger, all our front hair, you know. And all our faces were bright yellow – they used to call us canaries.”

The Canary Girls, as they became known, didn’t just suffer with a change in skin colour though; TNT poisoning also meant coughs, chest infections, digestive problems and ultimately could lead to death. It is estimated that around 400 women lost their lives due to TNT poisoning during the war.

However that wasn’t the only risk the munitionettes faced. Many were also exposed to asbestos, some were injured in accidents with the machinery and in addition there was the ever present danger of explosion. Strict rules about dress made sure that no hair clips, brooches, combs or cigarettes – nothing that could cause a spark – were allowed into the factories. Another worker, Kathleen Gilbert remembers,

“You all had to change when you went in. You had to strip and change into other clothes because you weren’t allowed a little tiny bit of metal on you at all, not one hook or eye or anything. And of course they had corsets in those days with wires in them, you see. And you had to finish up with an overall and put your head covering on.”

Workers had to wear dog tags which would be used to identify casualties in the event of an explosion. Sadly there were several big explosions in munitions factories where many workers lost their lives. The biggest of these was at the National Shell Filling Factory in Chilwell in 1918, where 134 died and another 250 were injured.

Despite the dangers women rose to the challenge, learnt new skills and formed a vital part of the overall war effort. By the end of the war it was estimated that around 80% of the weapons being used at the front were made by munitionettes. It’s clear the impact that their service had, as Hal Kerrige a soldier recalled:

“Well, at one stage for every shell that we fired, they fired a dozen. Oh we were overwhelmed, there’s no doubt about that…So they removed all the restrictions about women labour, said, ‘You can employ women wherever you like on whatever you like, whatever they’re capable of doing – put ’em in the shell factories.’ And that’s when we started to get shells and shells and more and more and more shells. And they were a saviour, they really were. Because if they hadn’t removed those restrictions about the employment of women labour, we’d have been in trouble.”

At the end of the war the vast majority women were forced out of the factories, particularly married women who many thought should not be in any type of work. There was a great emphasis on jobs being available for the men returning from the front, to the extent that even some jobs which were traditionally female-held positions were now turned over to men who had returned with injuries.

The Government gave a somewhat token gesture of thanks with the Representation of the People Act of 1918, granting some, but by no means all, women the vote.

Despite this it is easy to see how the attitudes and expectations of people slightly shifted as a result of the amazing work the women did during the war, including perhaps their own ideas about what they were capable of.

The munitionettes played a crucial part in Britain’s efforts during the First World War. When we remember the servicemen who laid down their lives, let’s not forget the sheroes whose names have been forgotten, who remained at home and gave their all, including sometimes their lives.

Find out more…

There are so many fantastic resources where you can find out about the munitionettes!

This post originally appeared on the Sheroes of History blog. Sheroes of History is an exciting project telling the fascinating stories of history’s forgotten heroines. The aim of the blog is to raise the profile of these incredible women and provide a broad range of inspiring role models for girls growing up today. If there is a Shero you would like to write about for the site you can get in touch and submit your idea. Follow Sheroes of History @SheroesHistory and like them on Facebook for loads more women’s history updates!